Everything comes with a t-shirt these days. If you run a 5K, you get a t-shirt at the finish line. If you donate to a charity, they’ll mail you a t-shirt (or a tote bag—don’t get me started on tote bags). If you volunteer, attend a family reunion, if someone’s getting married, or you’re a fan of a sports team, musician, band, brand, or someone on the internet: you can bet there’s a t-shirt for that. Some of these t-shirts are worn for one day then never worn again—they’re situational. Sometimes those situational t-shirts transcend their initial use and become paint shirts, knock-around shirts, or sleep shirts. But many of these t-shirts don’t get repurposed. They sit in a drawer for a decade like the plastic cutlery from take-out that lives in the silverware drawer alongside real forks and spoons, languishing somewhere between useful and useless. Eventually, most situational t-shirts get bagged up and donated to the thrift store, if they’re not laid out for free on the sidewalk, or worst of all possibilities, put straight in the trash.

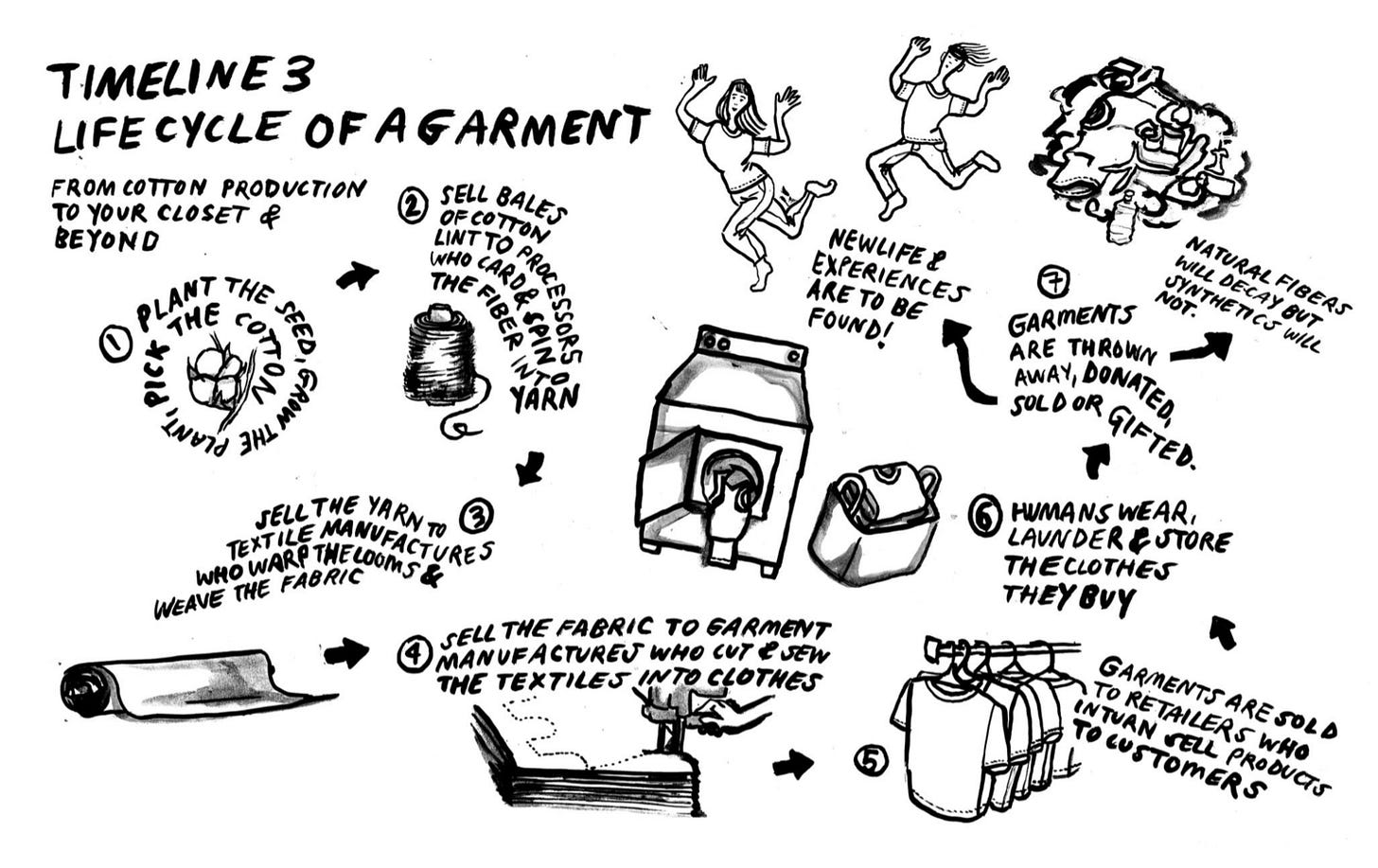

Throwing a t-shirt in the garbage is throwing away all of the time, energy, labor, and natural resources it took to make that t-shirt in the first place. Dozens and dozens of parallel industries are involved in garment production—from design, to farming, to shipping, to manufacturing, to construction, and beyond—it takes a massive amount of resources and coordination to produce a single t-shirt. Take farming, for example.

To produce just one cotton shirt requires approximately three thousand liters of water. Textiles production (including cotton farming) uses around 93 billion cubic meters of water annually, representing 4% of global freshwater withdrawal. (The Conscious Club)

Cotton production requires land, soil, water, chemicals, human labor, picking equipment, processing equipment, and more. Cotton plants must be germinated and cultivated, mature cotton fibers must be removed from the plant and processed (often bleached) before being carded and spun into yarn. Cotton yarn is then warped onto an industrial knitting machine to be knit into yards of jersey knit fabric which might be dyed before being bolted and shipped to a factory where the fabric is cut and sewn into t-shirts. Those t-shirts might be dyed, embellished, or printed before they’re packaged and shipped to warehouses who distribute to retailers or direct to customers. Multiple nations contribute to the production of a simple t-shirt. Cotton grown in the United States of America might be processed in India, then turned into fabric in China before it’s shipped to Bangladesh to be cut and sewn into t-shirts—that are sent full-circle back to the USA to be sold.

The issue of textile waste is not solely the responsibility of the consumer. A lot of waste is generated in the process of cutting and sewing a t-shirt. Every positive shape of a garment has a negative—the curve of a neckline creates a half circle of wasted fabric that gets thrown away. As a result, 15% of all materials are tossed out in the process of garment construction. If 15% of the fabric is trashed in the production of a t-shirt, imagine what that means when that t-shirt ends up in the garbage: 100% of that fabric, 100% of the time, energy, human labor, and natural resources, is wasted. It’s as though all those farmers, processors, designers, cutters, sewers, shippers, and retailers did all that work for absolutely nothing.

But hey, sometimes, large fashion brands create this kind of waste, by choice, all by themselves:

A staggering 30% of all clothes made around the world are never sold. It's one of fashion's “dirty open secrets” that many retailers destroy, landfill or incinerate the clothing that was never sold and has never left the store to make way for new merchandise, creating a serious waste problem. (PIRG)

And as I go through modern existence, constantly offered one disposable, single-use t-shirts after another, these statistics haunt me. It was inevitable that I had to confront their reality head on.

My aunt is a self-identified hoarder. Her two main collections are clothing and holiday decorations. She decorates each month for a different holiday—and the months without holidays, well she has decorations for those too. Strawberries in June and sunflowers in August. In 2022, my maternal grandmother, or “Gma” as I called her, was diagnosed with bone cancer. She was a twice survivor of breast cancer, and at 94, was not interested in putting up a third fight. At that time, my aunt stored her clothing collection at my Gma’s house—dozens and dozens of plastic totes with garments neatly folded inside, organized by type or era. (Not to mention the walk-in closet and additional racks of clothes, all chalked full.) I volunteered to assist my aunt in downsizing her collection because I wanted to see what she had, and what I could score, but I also wanted to spend time with my Gma in the few months I had left with her.

On the first day, my aunt dragged a bin out of the back bedroom into the kitchen. She showed off garment after garment to my Gma and I. We would then say whether or not she should keep each piece: not that my aunt heeded our suggestions. At first, I was salvaging only the vintage that had resale value and the pieces I personally wanted to wear or work with, then bagging up the rest to donate. My aunt was 20 in the 1980s—she taught aerobics, skied, played tennis, and apparently spent all her money on Nordstrom’s lingerie and swimsuits. Suffice to say, she had a lot of great vintage to sell. But by the end of day 1, we still had 2-3 FULL black trash bags of donations, and I thought: donating all of this is not the responsible thing to do.

Carting those bags and bags of clothes off to a thrift store would not have guaranteed that each garment would be put on the rack and resold. Often the thrift shop is just one stop on a garment’s journey towards being bailed up and shipped to a developing nation, already collapsing under the weight of waste colonialism.

This is where I come back to that issue of situational t-shirts. I had hundreds and hundreds (no joke) of t-shirts from my aunt now, and I needed to find a way to resolve the storage problem they created in my studio. This is how the 3T method* was birthed.

3T is three t-shirts deconstructed, stacked, sewn, sliced, then reassembled back into a t-shirt, now 3x as thick. It’s a take on the classic chenille technique. The methodology behind 3T is also rooted in the radical acceptance of the ubiquity of the t-shirt. I choose to accept that this item that exists, has been orphaned, and needs resolution. It's ok to have donated or thrown away clothing in the past. The goal is progress not perfection. Nothing sustainable comes from forcing behavioral changes. But by unifying these garments, it validates their existence, and strengthens their otherwise weak physical presences on their own.

T-shirts are often made from lightweight jersey which means holes can easily form when sewing this kind of secondhand material together, especially if the tees have already experienced a decent amount of wash and wear. The aesthetic elements of 3T—hanging threads, vertical slashes, rough edges, sporadic holes—both emphasizes and celebrates the temporality of the material. The scrappy nature of 3T also nullifies the specific branding of the 3 t-shirts in each piece, so that the words and graphics become like a foreign language, in the same way that layers of wheat paste posters, weathered and peeling away from plywood, become more about texture and shapes than the individual graphics of old movies and past events.

No one need be reminded that waste is a massive issue in our world today, but what falls by the wayside is the reality that waste happens on both sides of the material equation. Pre and post-consumer textile waste compounds the futility of producing clothing in a society where textiles have the value and longevity of Kleenex. This is an issue, in part, because fast fashion has so flagrantly devalued the labor of garment workers behind the machines, hard at work creating their product, that they are selling pieces at prices far lower than the true cost of production.

As a human, I don’t believe in giving advice. As an artist, I can only share my experience. I feel a responsible for the way I engage with the material world. For environmental, ethical, and financial reasons, I commit myself to repurposing as much secondhand material as possible. I hold reverence for everything contained within a garment; all of the time and collaboration between human hand and planet earth—even if what results is a polyester t-shirt created solely to be worn by volunteers at an Earth Day event (the irony).

My hope is that considering and questioning our modern methods of garment production and consumption can lead to a mindset shift: a move away from convenience towards acting in ways that solve problems. This is what spurs on new aesthetic and methodological developments such as 3T. I consider it my duty and (most of the time) my pleasure to make my work and to serve our planet in this way.

*Watch the 3T method in action here.