Madness Behind the Method

The Zero Waste Methodology in work and life is mostly “progress, not perfection”

The full title of my brand JRAT is “JRAT Zero Waste” because the zero waste methodology has been the cornerstone of my practice for over a decade. I learned about the method from my professor, Timo Rissanen, while attending Parsons School of Design and have never looked back.

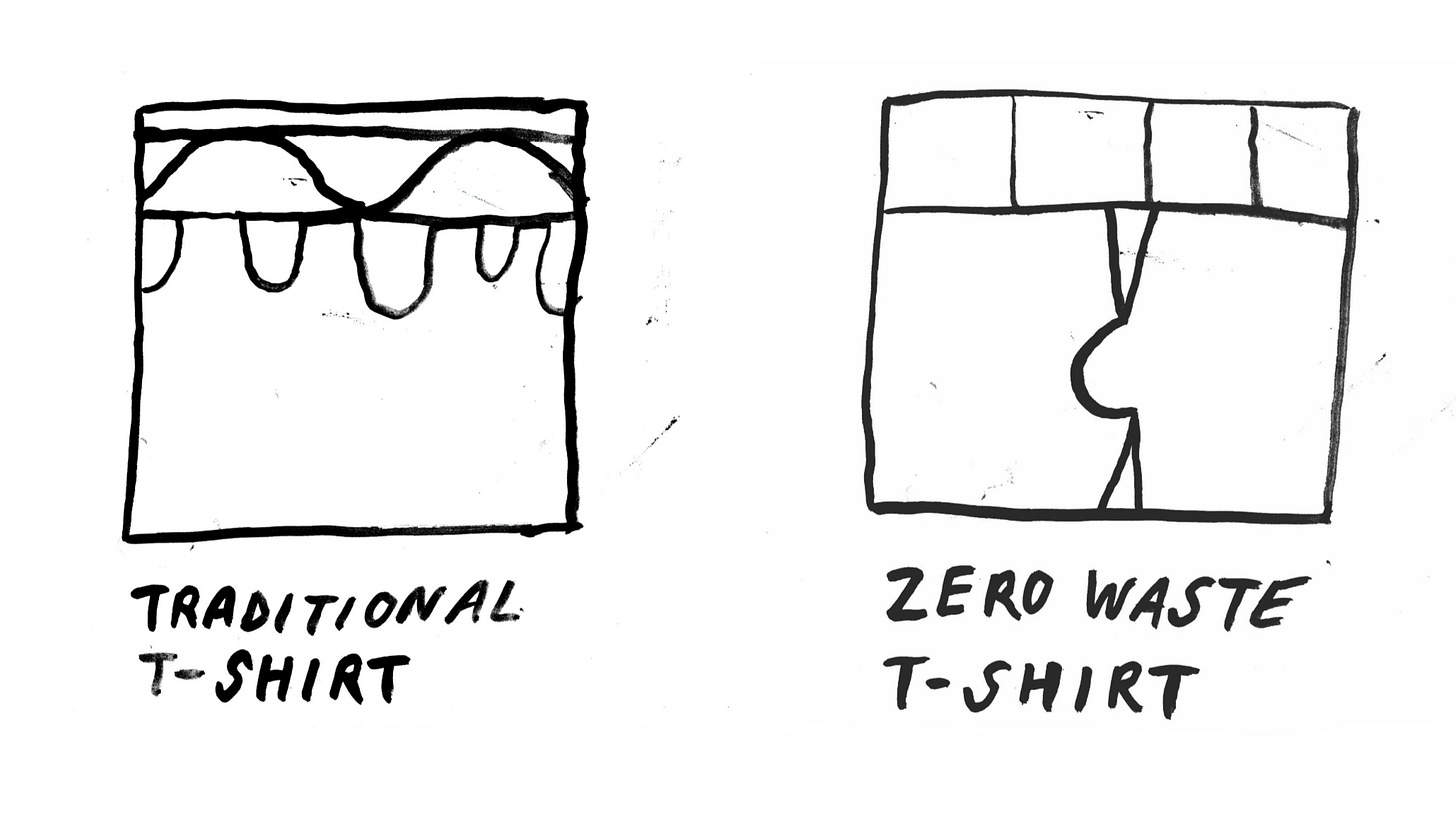

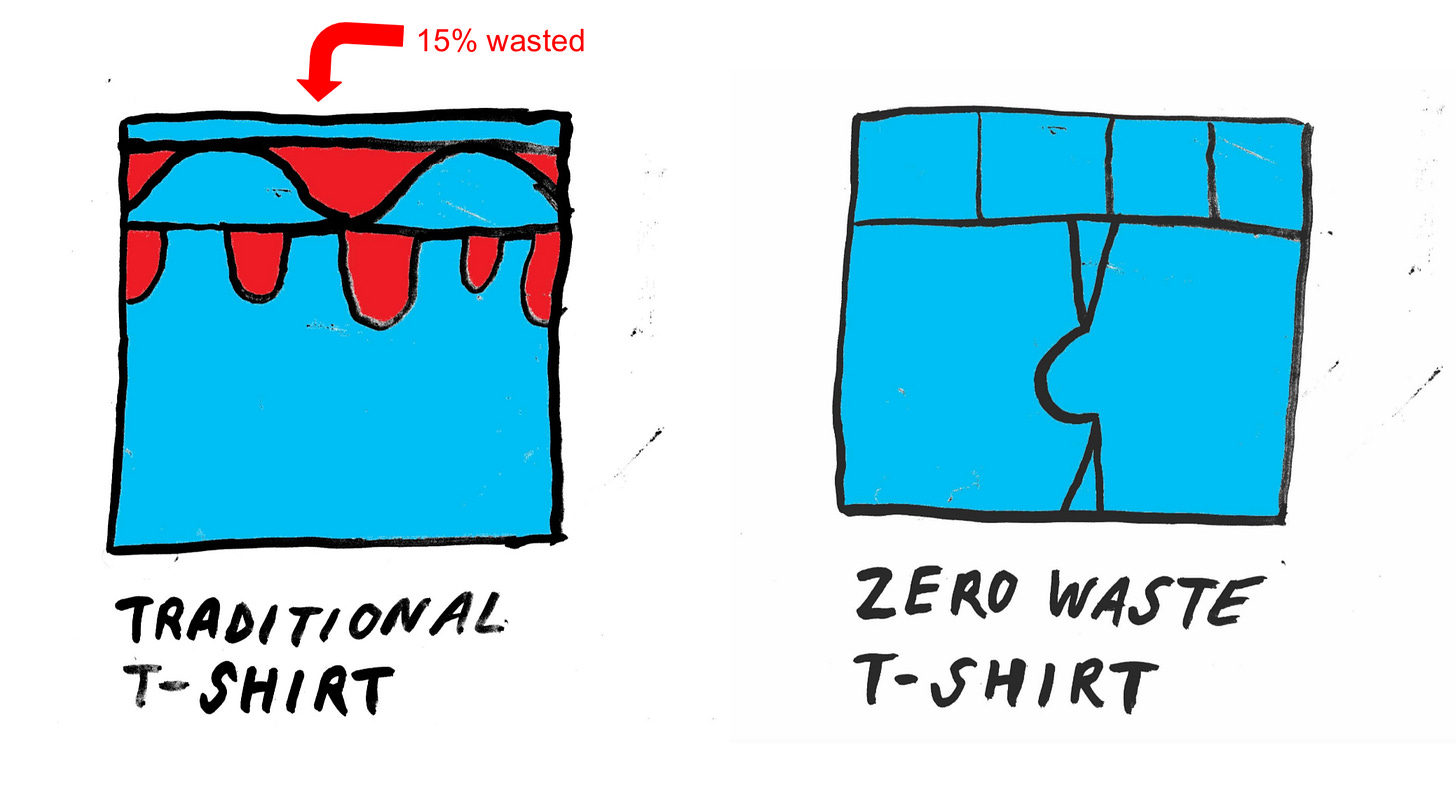

The principle of zero waste pattern drafting is simple: create a garment pattern that wastes no fabric. If a zero waste garment were to be disassembled, it could return to a perfect rectangle or square of fabric. Traditional pattern drafting methods, comparatively, waste about 15% of all material. For every positive shape, such as the curve of a neckline, there is a negative half circle of material that gets thrown away—a disservice to both the material and the consumer, as they are the ones who foot the full bill for the yardage used to make a garment regardless of how much of that material is trashed in the construction process. In my opinion, zero waste patterning is the most ethical, sustainable, and honest way to approach garment production. It preserves the fabrics integrity, honoring the totality of the materials—the time, energy, and natural resources imbued within— by utilizing every available square inch.

Where traditional patterning methods drafts individual pattern pieces (a blouse front, back, and sleeves, for example) to be laid out as a “marker” (the orientation of pattern pieces on the fabric to be cut), zero waste patterns germinate from the standpoint of the marker, like giant puzzles pieces: every pattern piece fits neatly into the next. Thus, to increase the width of one pattern piece, those adjacent must decrease in width. To change the curve of one pattern piece is to adjust the neighboring inverse curves, and so on. This is where the complexity of the method becomes exponential.

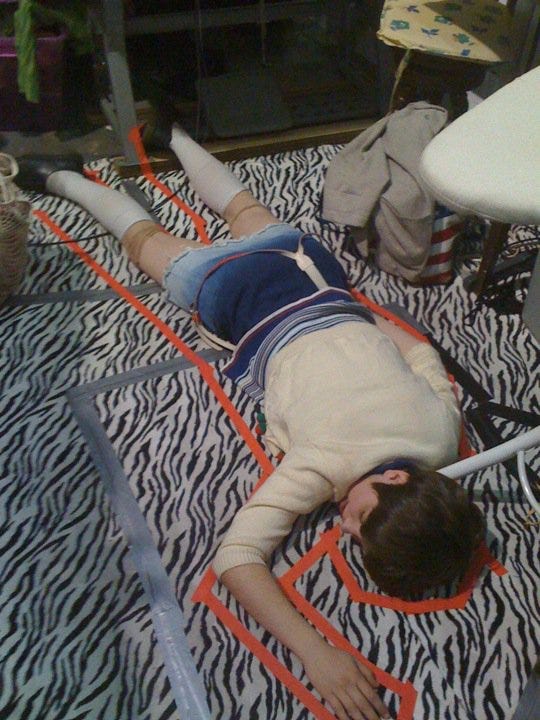

Both traditional and zero waste patterning intend to achieve a specific outcome, most often determined by something like a croquis or flat. A “croquis” is a fashion illustration where the garment is drawn on a body—a “flat” is a technical illustration of the garment off the body, laid out flat. When I was in school, we were tasked with executing both types of illustrations for our conceptual projects, but I often found myself sketching croquis after croquis that looked exactly the same. I ultimately determined that my creative energy wasn’t intellectual so much as it was physical. New ideas were intuited through the act of making as opposed to through forethought contemplations. Zero waste patterning fit in well with my action oriented design process, as it allowed for mysteries, like blocks of unused fabric, to be resolved through the process of reconfiguring square fabric into human forms. There’s an aesthetic freedom in allowing mistakes and problem solving to fuel creative agility and elasticity. Even today, I often have to relinquish some control of outcomes to the process. As a result, I continue to discover new proportions, shapes, silhouettes, styles, and construction techniques that I would not have discovered without adhering to creating no waste. A chunk of unused fabric within a marker could become a functional design element like a pocket, or an aesthetic design element like more (and more) ruffles; fabrics transmutability is limitless.

Another element of my design practice is that I don’t engage in a “traditional” sampling process. Where some designers create muslin samples that serve the purpose of refining the final product, but ultimately become waste—my muslins become finished garments because I risk using my intended fabric right out the gate. If you’ve bought a garment from me, it might’ve been the first time I cut and sewed a zero waste pattern. (Or it might’ve been the result of salvaging a failed pattern.) I draft, cut, and test patterns that sometimes fail, but zero waste allows for missteps to become revelatory opportunities. A large failed pattern can become a smaller, successful, more densely embellished garment, and sometimes I have to cut a garment up into shreds and sew it onto a backing with other scraps and seams just to make use of a failed attempt. In the world of JRAT, a collection is considered complete when all materials curated for that collection have been utilized. Since my ultimate intention as a designer is to be zero waste by using every last scrap of material, my meter of success is determined by my ability to conceive work within the parameters of these ethical values and commitments.

Zero waste drafting is a challenge that I’ve accepted whole heartedly. Over the past several years, I’ve begun to approach more aspects of my life with this same revelry in and dedication making use of what could otherwise be considered waste.

I started JRAT in 2020 during the pandemic, when, like many people, my life was falling apart. The three jobs I had maintained in order to pay my bills disappeared. I was a tour guide, a chair weaver/studio assistant, and a yoga instructor. Tours paused, the artist I worked for moved away, and the yoga studio folded. My marriage was in a precarious state. A seven year long collaboration I had conducted with a friend came to a painful end. Most of my creative identity had become wrapped up into that project, so now that I had no job(s), no artistic outlet, and very little support, it felt as if years of effort had come to a complete waste. I had to figure out how to build back my life and my work from scratch.

A decade earlier, I had experienced a similar level of total disintegration. The same school year that I learned about zero waste drafting, I curated an art installation with my roommate. We had come to a point of contention in our relationship, but we were still trying to cooperate on the project. I didn’t possess good emotional regulation skills in my early 20s which made the situation feel personal and overwhelming. Nonetheless, we put the installation together and called it a success. When it was time to deinstall, her parents had just come into town and she was staying at their hotel instead of our apartment. I texted her asking what time she was going to begin deinstallation the following day and she didn’t respond. I texted again explaining that I needed to get this done sooner than later, but still she didn't respond. The next morning, I contacted her for a final time, and with still no reply, I made the decision to go to the gallery early and begin deinstallation on my own. That’s when she showed up—with her parents, who had not yet seen the installation. And now it was halfway off the walls and onto the floor. Her dad left the gallery crying. My roommate just stood there in disbelief. Her mom tried to smooth over the situation but there was no salvaging it. I had no idea that her parents had not yet seen the installation and profusely apologized for having made an assumption and thus this mistake. My roommate just walked away, without saying a word. She never spoke to me again. Even though we continued to live together, even though I tried on multiple occasions to apologize face to face. I wrote her letters and messages apologizing again and again. She never acknowledged me, and to this day, she has not spoken to me.

That experience was crushing. I went into the summer before my senior year absolutely deflated. It felt as though I had been outed as a horrible person and there was nothing I could do to defend myself or reclaim my self-image. This edict had been placed upon my head, and now anyone who had something positive to say about me, I considered a liar because they obviously had not yet experienced the truth of my character. Who I was was the worst of me, seen and interpreted through the eyes of my former roommate. I was ill equipped to process and recover from an unbearable sense of guilt and shame. Instead, it became a trauma that haunted me for a decade.

I developed an eating disorder shortly thereafter. Perfectionism had been one of my maladaptive coping tools. In this new adaptation, perfecting my body through manipulating and restricting my relationship with food, I attempted to ensure that I would never do wrong by anyone, and thus never again could I be held in contempt. I started to isolate myself and struggled to maintain old friendships—I feared establishing new friendships, thinking they would come see me just as unforgivable as she did. My senior year I worked on my thesis, exercised, and starved. I graduated top of my class and totally depleted. On the day I was supposed to attend graduation, I decided to ride my bike to Breezy Point instead. Along the way, one of my pedals fell off and my tire went flat. Instead of walking my bike home, I threw my bike off a bridge and ran.

I kept on running. After graduation, from Chicago to Seattle to Helsinki, Finland where I spent three months sewing white t-shirts in the Amos Anderson Museum for Timo Rissanen and Salla Salin’s installation, “15%”. I then moved back to Seattle where I became a tour guide, a chair weaver/studio assistant, and eventually a yoga instructor too. I embodied the shame of my mistake and allowed it to limit my ability to make friends, pursue my desired career, and live happily. My self-image was chained to a twisted perception conceived through trauma. Over time, I disengaged from the things I loved because I could no longer understand how to engage joy. My life was now work and little else.

It was in 2020, when I lost my work, my most powerful distraction, that I finally became ready to face head on the specter of my pain—I had been carrying it around with me like the bags of discarded clothing stuffed into my studio closet. It’s not that these things have been wasted so much as they’ve not yet been utilized. Nothing is truly wasted, so long as I choose to make use of what I have. I chose to begin a journey to utilize my pain as my path towards healing. Instead of walking alongside it, I chose step by step to stumble through it. The worst of experiences became puzzle pieces that fit together to better build a more clear image of what I had been through, and thus how I could recover. I have finally come to understand that the best of me has always been, and will always be, just as much a part of me as my worst. I am both, because I am human. I was and am allowed to be human, just like everyone else.

The difference between rebuilding my life post-disintegrating in my early 20s vs. in my early 30s was that the usefulness of my maladaptive coping tools had finally run their course by 2020. Denial, perfectionism, restriction, over-work, these things no longer served me. By the pandemic, I started to see how they kept me stuck, and reverberated my pain. I live today in the comforting and uncomfortable, the clear and murky realm of the dialectic: I am doing the best I can and I can always do better. It’s progress not perfection in both life and work. Zero waste patterning will always be a journey of refinement by trial and error. It’s a path of unabashed exploration that asks me to accept mistakes as an invitation towards discovery. I am allowed to make mistakes—they are not a moral indictment against me. They are an opportunity to learn. I can ask for forgiveness, and when denied by others, I can find a way to give myself the grace and empathy that I deserve. I have forgiven myself for that fateful mistake my younger self made, even if my former roommate cannot. And that’s ok. I will not hold it against her because I choose to no longer hold my imperfections against myself.

Thank you for sharing this, it must have been hard to write about these things! I can really relate with the urge to perfect/refine/restrict--the feeling that if you "labor" in just the right way and deny yourself, you can make yourself acceptable.

Perhaps that is why handicraft is so healing--it takes that same deep urge for labor and sacrifice, but instead of restricting, you are making an addition, including, welcoming. Saying "yes" to something odd and imperfect and exuberant. The same madness, but turned inside out somehow.

Thank you for writing this piece and for your kindness to your past self--it makes me feel very encouraged and not so alone. 💟