84 Hours Later

My experience sewing 14 hours a day, 6 days in a row

The metric of success that I devised for my performance, 14 Hours, was simple: sew for 14 hours a day, 6 days in a row. I wanted to embody the lived experience of garment workers around the world, but more specifically, in Bangladesh, as they are some of the lowest paid and most vulnerable to exploitation and unsafe working conditions. I wanted to answer some questions for myself like—how does it feel to sew for 14 hours a day, 6 days a week? What are the effects mentally, emotionally, spiritually, physically, relationally? What does life look like when your work week is 84 hours?

I chose to work myself more than what is “legal” in Bangladesh—though they recently raised the maximum weekly hours from 60 to 72. (“Legal” because even though there are laws in place, they aren’t strictly enforcement and factories aren’t rigorously monitored. And lord knows the fashion brands who employ these production facilities aren’t going to lay down the law when breaking it is to their benefit.)

For many garment workers in Bangladesh, a 72-hour work week is simply the reality they have become used to, in part because the wages they earn during a regular 48-hour workweek are not enough to subsist on. (Source)

Additionally, I intentionally chose to pay myself less than the current mandated minimum of roughly $4.70 a day. I paid myself $3.50 per day, making $84 a month with a 6 day work week. Garment workers around the world continue to fight for fair and livable wages, but they are routinely denied. In late 2023, garment workers in Bangladesh were protesting in order to raise their minimum wage to $208 per month to keep up with cost of living and inflation. They were only offered a 25% raise to $90 per month which led to increased violence at protests and the death of 2 garment workers. Eventually the protesters made some gains when the government announced a 56% raise to $113 per month—half of what they originally requested.

Low wages in Bangladesh factories have led to the growth in the country's garment industry as garment production and exports account for nearly 16% of Bangladesh's GDP.

Bangladesh employs 4 million workers across 3,500 factories and is currently the second-largest garment-producing nation behind China. The country's factories supply many large clothing brands such as H&M and Gap.

Factory owners have hit back at the protesters' demands, saying that production costs are higher because of rising energy and transportation costs, and that Western brands are offering to pay less for production. (Source)

Though I designed my performance to have me working slightly longer hours, at a slightly lower wage than the laws of Bangladesh permit, I ultimately afforded myself a variety of luxuries that real garment workers do not enjoy:

I set my own hours, choosing to work from 6AM to 8PM each day

I designed my own projects and methods

I made changes to the production plans day by day, as needed

I set my own daily production goals

I had no quality control

I had no management or monitors other than my livestream keeping me accountable

I gave myself a 5 minute break every 2 hours with a 20 minute lunch break at noon and an optional 10 minute dinner break at 6PM

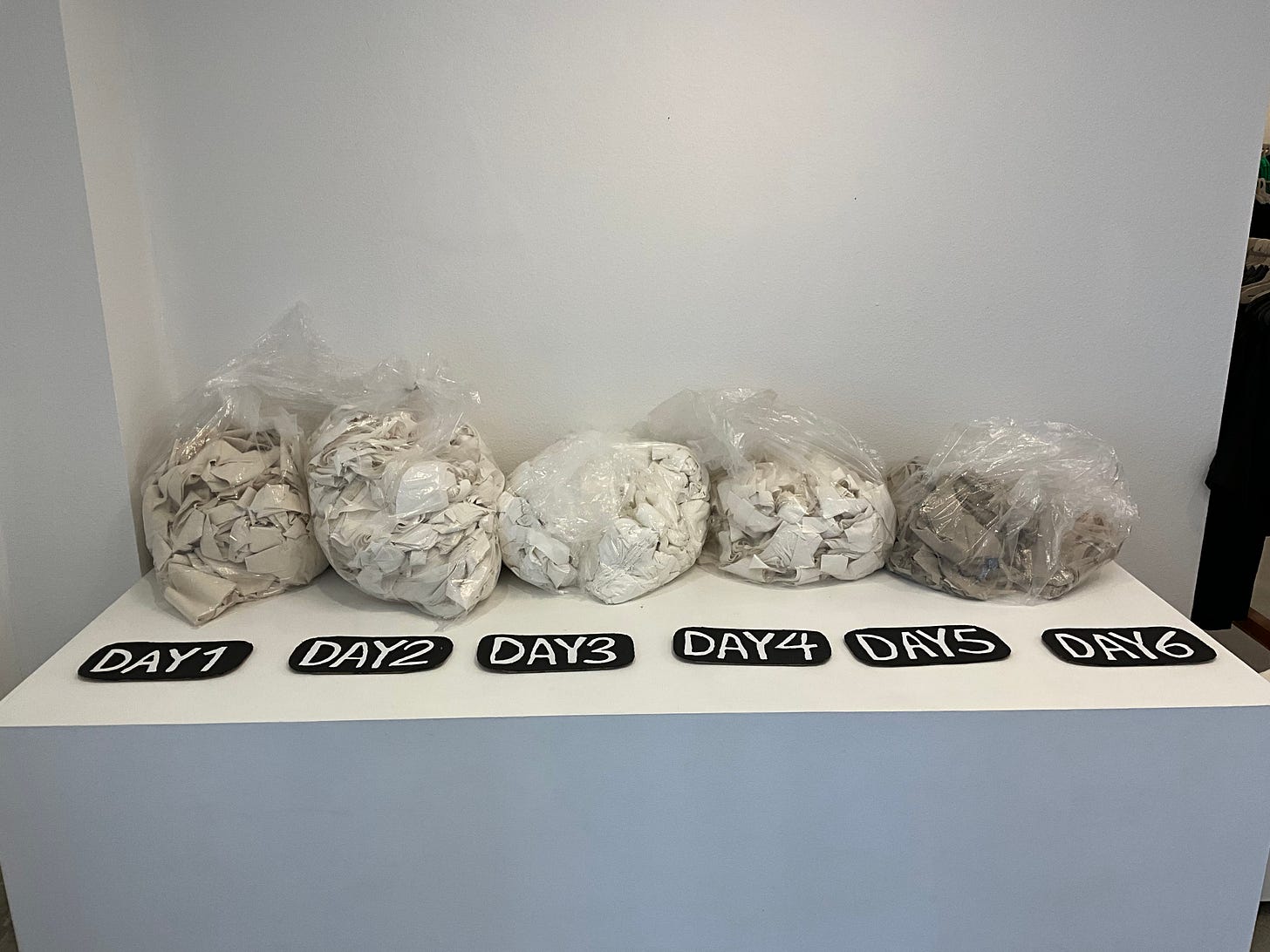

In planning for this performance, I initially intended to sew two pieces of fabric together in straight lines for 14 hours, producing one “tapestry” or “quilt” per day. The finished pieces would then be included in an exhibition next year and at a later date, they would be auctioned or sold to raise money for garment workers rights and reparations—with $3.50 withheld in order to compensate for my daily labor. However, because I allowed myself a great deal of agency in executing this performance (so long as I kept to sewing 14 hours a day for 6 days in a row), I was able to partner with Prairie Underground who provided me with a space to work in, a machine to sew on, and a new source of material to work with.

Prairie Underground has been designing and producing garments in Seattle since 2004. They started their business around the time my parents closed theirs, so in a way I feel as though they are carrying on the legacy of Seattle garment manufacturing that my parents contributed to for over 20 years. Almost 80% of Prairie Underground’s production is done in house, with the remaining 20% coordinated through contractors working out around the greater-Seattle area. Since they cut in house, they had production scrap on hand while I was installing for my performance, which revealed an new opportunity. Aside from raising awareness, this performance could aid in reducing production waste. So my plan morphed to sewing Prairie’s textile scrap onto a backing through a variety of textile manipulations each day. At the opening event on April 13th, I sampled a variety of techniques—each one involving straight sewn lines so as to ensure I would be doing something repetitive if not monotonous while sewing for 14 hours.

In the weeks leading up to the performance, I experienced a lot of anxiety. I feared I wouldn’t be able to wake up early enough and have enough energy to ride my bike 26 miles round trip each day (another stipulation of my plan, considering $3.50 daily wages would not be enough to even take the bus round trip, let alone own a car). Even though I used to commute 100-150 miles a week, back when I worked 4 jobs, I haven’t had biked that much since the pandemic. I also I wouldn’t wake up on time, or have time to take care of my basic needs like eating, bathing, resting. And how was I going to maintain my most important relationships amidst working 6AM to 8PM?

My fears aside, Day 1, April 15th finally came. The following are excerpts from my “diary”, written between April 15th and April 20th, 2024:

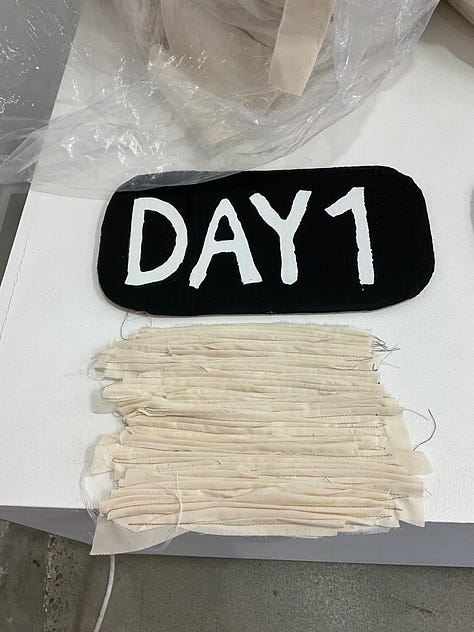

Day 1: PLEATS

Left the house without keys, rode 20 blocks, rode back, broke into apartment building, had to wake up Brian at 4:45am so I could get my keys then rode hard to make it to PUG by 5:45

The internet wasn’t working so I had to buy pass

Sewing actually felt rather good for the first 10 hours

Hit a wall just before 4pm. Felt myself slowing down

Was fighting with the material so I flipped my backing around and started working from the other side

Found a goal: try and get to the part of the fabric where there’s an oil stain and cover it up—this gave me some purpose for the last 4 hours so I sped back up

When I made the decision to do this performance, we lived 7 miles away from PUG, but then we moved 6 miles farther north so that my commute became 26 round trip instead of 14

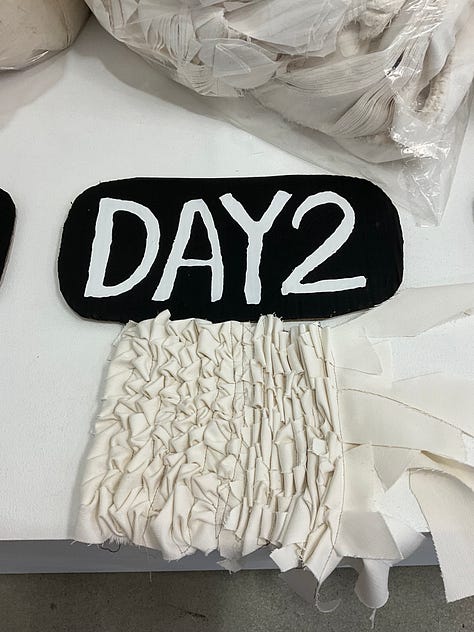

Day 2: SEWN STRIPS

Woke up at 3 to get to work by 5 so Andrew could set up camera

Rear light died on my ride

One of the garment workers brought me egg fu young and granola bars! Felt really humbled by her generosity

New textile manipulation method is going faster

Stomach is upset most of the day

Hit a wall after 4 hours, struggled to get to lunch time

Felt renewed after lunch but hit a wall again at 4PM

Had a lot of different songs floating in and out of my head including Limp Bizkut but just the part “Keep rolling, rolling, rolling, what??”

Finished 20 min early because fighting with material too much, couldn’t add any more so I cleaned instead

Got a troll on Twitch “could be pants could be a curtain…who knows” she also said my website sucked and looked like “shitty kids drawings”

Andrew on time but we chatted so I left 20 mins after 8PM

Felt wobbly trying to get bike in the door

Went to bed at 11

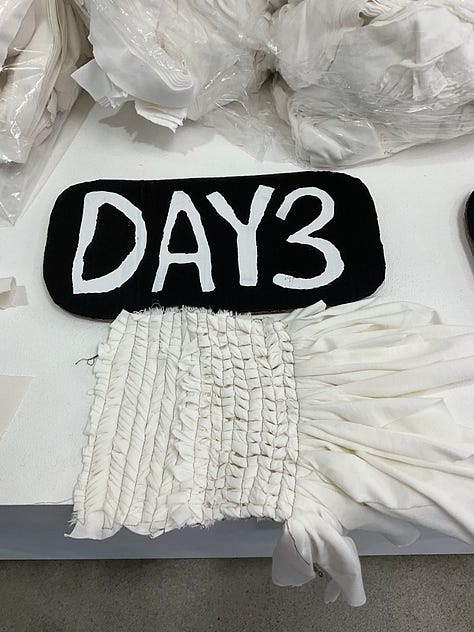

Day 3: TWISTS AND FOLDS

Felt a little rushed out the door bc I lounged on the couch and crafted an IG post in the morning

Made it to work on time, had some bumps in getting my method going and needed to find scissors

Kept counting the hours and noticed I was feeling drained 4 hours in

I think it’s interesting that people are so concerned for me. Why aren’t they more concerned for the women who actually have to work like this for a living?

Noticed my eye sight get blurry or unfocused a few times throughout the day

Started to notice my hips and neck feel sore, uncomfortable in my chair, had to stretch

Wanted to get up and use the bathroom every 1.5 hours just to move and not sit for so long

My stomach was upset all day too

At lunch time I wasn’t hungry enough to eat more than half my salad

I decided the day before to sew quilting squares because I had found a stack in the scrap and I was also tired of fighting with pushing long yardage through the machine

There’s a point every day, half way or more, when I felt really drained and fatigued and feel myself slow down, and it’s followed by a renewal of energy at the last 4 hours where I regret losing some time to my sluggishness and feel compelled to speed up to make up for that lull. My quality goes down at this point which is a luxury I have that garment workers don’t. They have to be precise all day whereas no one in quality control is telling me to keep the same level of precision the whole day through so I am allowing my work to look sloppy to express my depletion of energy, attention, and willingness to work (even though I force myself to continue working)

I finished with enough time to sample a few different textile manipulations and amend my production schedule for the rest of the week (another luxury I have that a real garment worker doesn’t) I am setting the rules as to what I need to complete, how much, and by when, whereas a real garment worker would have all that assigned by them via a supervisor who is under obligation of a client's wishes and timeline.

The ride home was more manageable, and when I got home Brian had bought us Chinese food!

Went to bed at 10:40PM

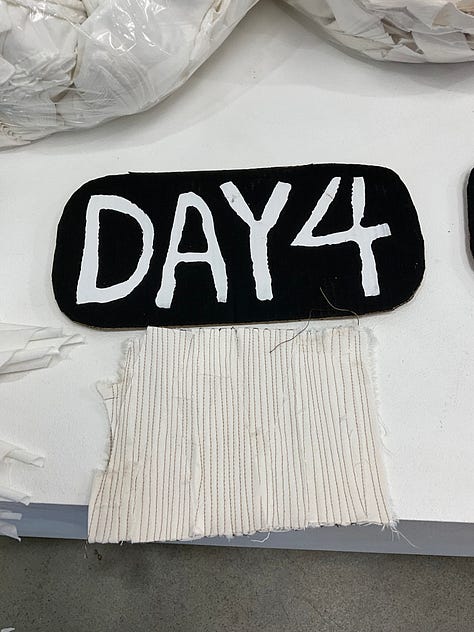

Day 4: LOOPS

Set off the alarm and it took 15 min to get it turned off

Really noticed my fatigue off and on throughout the day

Realized why people drink coffee—craved caffeine! Eventually found some black tea

Felt slow

Had a group of art grad students come visit at the end of the day

I’m not hungry

My stomach is upset

People keep thinking the money on the floor (representing the $3.50 I earn each day) is actually donations, someone doubled my weekly pay by dropping me a $20.

I want my stitches to show the emotion and energy of the experience

I am enjoying the commute but the hours suck

Reminding myself that I have integrity

My dad texted me asking how I could afford a phone on less than $4 a day haha. I told him “I’m not a method actor”.

This feels synonymous to driving for 14 hours a day, 6 days in a row—a concept or feeling that most people could viscerally understand the exhaustion and drain at the end of the day (and the fear faced with waking up and doing it again the next day, and the next)

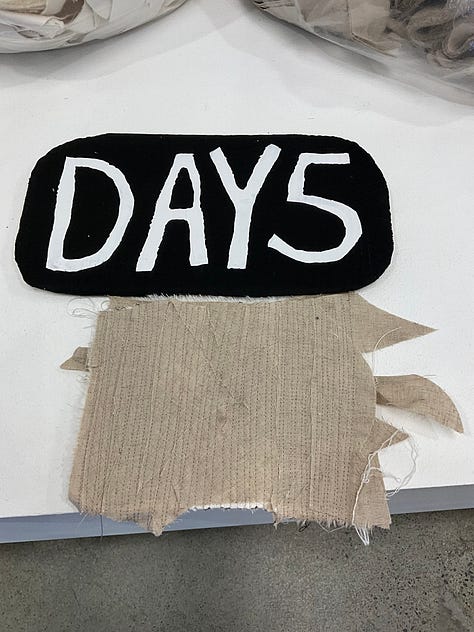

Day 5: STRAIGHT LINES

I saved my original method for this second to last day and its the easiest to manage

I like how the progression of my pieces shows the emotion behind the experience—moving from unmanagability to acceptance

During my work today I had a lot of thoughts, but now at 10PM it’s all just a blur

Day 6: RUFFLES

I thought today would feel harder bc I'm the only one here but it's actually gone faster. Giving myself deadline and quotas for the day actually helped too

The time passed by really fast

I sewed my last stitch exactly at 8PM

Every day I woke up at 4AM, left my apartment by 4:30AM to ride an hour south in order to change clothes, eat breakfast, and get set up in time to start sewing at 6AM. I took my brief breaks throughout the day, and tried to leave promptly at 8PM, because the ride home was 1.5 hours with more uphill than down. I arrived at 9:45PM if I was lucky, ate dinner at 10PM, in bed by 11PM so that I could wake up after 5 hours of sleep and do it all over again.

Day 1, I showed up ready to go. After the first 10 hours of sewing small pleat after small pleat to create a massive hourglass shaped, croissant textured tapestry, the novelty had worn off. Day 2, I was a little more trepidation and found my energy bottoming out after 4 hours of sewing layered strips. Everyday my stomach was upset—maybe from sitting, maybe from stress. On Day 3, I sewed three different textile manipulations onto quilting squares. I noticed my eyesight starting to blur and by then my hips, neck, and sinuses were sore (the latter from breathing in and blowing out all the fiber dust kicked up by the machine). Every day when I took my 20 minute lunch at noon I could barely finish half of my salad—noon also marked 8 more hours of sewing. It felt like a gut punch, as if though those previous 6 hours of sewing hadn’t happened. I started out Day 4 by setting off the building alarm. Day 5 was a blur. I expected Day 6, Saturday, to be the most excruciating, since the staff at Prairie Underground were out of office, but it turned out to be a refreshing day. (Maybe because I knew it was my last.) I felt like I pulled through the tunnel, returning to the novelty and excitement I had experienced on Day 1. My mom came to visit at lunch time with cake. We chatted as I sewed. Having amended my design plan the day prior, I used my last day to create something “iconically JRAT”. I didn't want to miss out on the opportunity to sew ruffles for 14 hours.

I chose textile manipulations that intentionally hide the stitches I was making in order to expose how labor of garment workers goes unnoticed—hidden, though blatantly in plain sight. Their labor is concealed under a veil of perfectionism, as they are scrutinized and pushed to create product with such precision that it dehumanizes their contribution to the work all the more. Clothing looks as though it were machine made, but human hands and feet are always needed to operate those machines. Within the performance, perfection was sewing for all 14 hours aside from my brief bathroom breaks. I accomplished my goal but the work expressed the emotional experience of the experience. There are rushed stitches, exhausted stitches, angry and absent minded stitches too.

The pieces I created during 14 Hours are beautiful and powerful. They possesses deep meaning, but the work is ultimately meaningless, in the same way that the labor of garment workers is meaningless. Throughout the performance, I kept thinking: “How would I feel as a garment worker, to learn that what I slaved to create had been dumped in the Atacama Desert? Discarded by the very brand that contracted my factory; my work, added to a pile of unworn clothing so large it was visible from space?” I kept thinking, “If I were a Bangladeshi garment worker, how would I maintain a marriage? When would we have time together unless we worked side by side? If we had children, how in the world would we manage to raise them, let alone care for them day to day?” Each day I spent sewing for 14 hours, it became increasingly clear to me that even though these garment workers “have a job, at least!” Yeah they do, but do they have lives? How can you live when all you have time to do is work? As an small business owner, I get to choose whether or not I continue to work myself long hard hours for little financial gain. I am making a choice to do this work and to live this life. Garment workers in Bangladesh don’t often have better work opportunities available to them—sewing 288 hours a month for $113 in cities where the average 1 bedroom rental costs $89 a month is the better option. This first iteration of 14 Hours, for me, has become an extended exercise in empathy. I felt the pressure, the anxiety, the fear of living life with only 10 hours a day to spare. I felt the drain of my humanity as my body and mind became a machine, working in concert with the sewing machine. I kept thinking, “It’s 2024. No one should have to work this hard for this little unless they are freely and proactively choosing to do so.” And that is a probably the biggest luxury that Bangladeshi garment workers lack which I possess: the freedom of choice.

Just phenomenal. You are one of the bravest people I know and truly an inspiration. This world and its doings-stitchings- make absolutely no sense to me. I work at SCRAP, a recycle, reuse facility for everything art donated by the community. I create billboard clothes among other stitched art creations-"This Is Not My War" and Ceasefire Now" are the two I just completed. I NBN so it is a waiting game to see what comes in that I can use. I will be thinking about your factory worker post all day and I will share it with my co-workers. You are so inspiring! I'll be watching for your next story. Ride safely! Take care of yourself! LOVE ALWAYS! Lise Lange

Inspirational action! Thank you for using your own body and work to show the world what's happening.